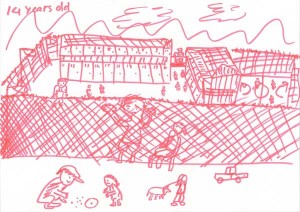

Image from In Their Own Words: 25 Drawings From Children In Detention

Blog post by Dr Helen Berents

“Australia currently holds about 800 children in mandatory closed immigration detention for indefinite periods, with no pathway to protection or settlement. This includes 186 children detained on Nauru. Children and their families have been held on the mainland and on Christmas Island for, on average, one year and two months. Over 167 babies have been born in detention within the last 24 months. This Report gives a voice to these children.”

This is the foreword of the Australian Human Rights Commission’s (AHRC) The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention (2014), which was tabled in federal parliament last week. The result of ten months of research this Report fulfils the AHRC’s commitment to follow-up their report, A Last Resort?, from a decade ago.

The findings are damning, both of this government and the previous Labor governments. Between January 2013 and March 2014 there were 128 incidents of self-harm and 171 incidents of threatened self-harm, 233 assaults on children, and 27 cases of voluntary starvation/hunger strikes. Prolonged detention, according to the Report, was inherently dangerous of children and “prolonged detention is having profoundly negative impacts on the mental and emotional health and development of children”. The full findings are difficult reading, and the recommendations made by the Commission —including the establishment of a royal commission—are worthy of more than the blame-shifting and politicking that has followed the release of the Report. There is much to unpick from the report, but I wanted to briefly pick up two points of discussion in relation to international and federal politics and justice.

Australia’s International Obligations

While last week’s report found some improvements in terms of absolute numbers, the AHRC was scathing of the ongoing treatment of children in detention. AHRC President Gillian Triggs has previously observed how Australia’s treatment of asylum seeker children is in breach of international law. The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has repeatedly expressed concerns over Australia’s detention of children citing its illegality under international law; the inadequacy of support and process; and the significant, ongoing, negative psychological and health effects of detention on children.

Detaining children should only ever be a measure of “last resort” and, crucially, “for the shortest appropriate period of time”. It must also “not be arbitrary”. Those words come from Article 37 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which Australia is not only a signatory of but was also centrally involved during its creation. When children might need to be briefly detained (for instance while health checks are being carried out) there are minimum standards for their protection, also set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child including that they “should be treated with humanity and respect”, “they should not suffer torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment”, and whoever is responsible for the child (parent or legal guardian) must protect them from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury, or abuse”. Across all these standards Australia has failed, the Report makes that perfectly clear.

Risk to Democratic Process

The government’s response to the AHRC’s report was also troubling. Prime Minister Abbott slammed it as ‘partisan’ despite it covering periods of both Labour and Liberal governments, and other ministers criticised the AHRC, President Triggs herself, and the media coverage of the report.

The response of the government—personal attacks rather than engaging the issues—is concerning for democracy, justice, and public debate in this country. The AHRC, along with other bodies are independent statutory bodies under Australian law. Danielle Celermajer, writing in The Conversation argues that “democracy is not a partisan issue”. The Australian Bar Association, the Law Council of Australia, and a group of 50 academics have all written statements or letters saying the attacks on the AHRC and Triggs herself undermine confidence in our system of justice and political processes.

Many experts are vocal about not only of what the findings tell us, the inadequacy of the government’s response, but also are expressing strong disapproval that the government has ruled out an royal commission into children in immigration detention.

There are complex reasons why people seek asylum, and in our contemporary world these issues are going to continue to become more complex and more pressing. Similarly, there are tensions between need to uphold security for all Australians and our national and international obligations to others. Triggs said “it is imperative that Australian governments never again use the lives of children to achieve political or strategic advantage…Australia is better than this.” The to the Report notes the way we treat asylum seekers “goes to the core of our identity as a nation”. The gut-wrenching, difficult findings of The Forgotten Children ask our politicians and all Australians to think carefully about how (and with whose suffering) we want to construct our identity as a nation. The stories told by the children themselves within its pages demand nothing less.

Comments are closed.